When I was teaching, I had a student one year who, no matter what I assigned, would connect the assignment to a horse. I taught sixth grade at a small school and the only subject I wasn’t in charge of was Music, so I enjoyed the efforts she went to in including a horse not just in writing and reading, but in math and science, too.

It probably goes without saying that this student, whom I’ll call Catherine, loved these animals, but I’m wondering now if her choice to study horses in all disciplines wasn’t just out of genuine interest, but it was a way to relate to the world. I knew Catherine when she was in middle school; a rather tumultuous time when kids begin to see the grey between black and white, and so much of their world feels upside down. Maybe Catherine used horses as something she knew to be a constant; if she could write them into the conflict of her stories, research areas in the world they thrive, or read about them struggling and succeeding in literature, maybe she could start to imagine herself in these situations. I doubt she was aware of it, but I wonder if her horses stood for symbols for things she didn’t want or was not able to express.

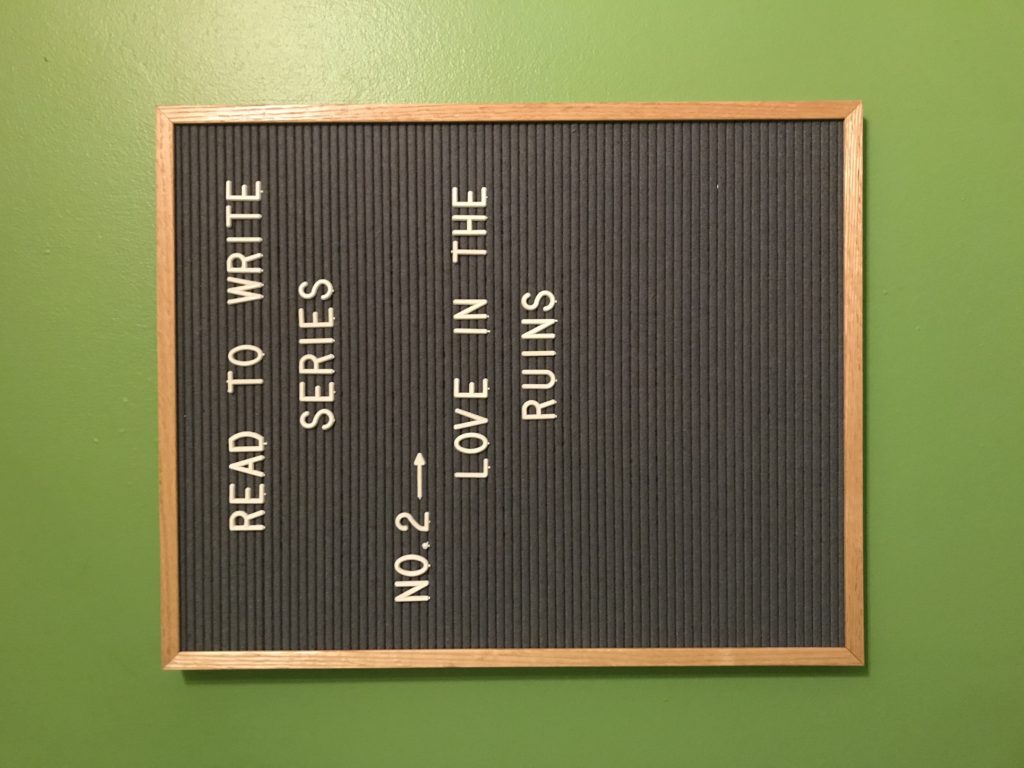

Such is the case with the martins Walker Percy uses throughout his book, Love in the Ruins. Each time Tom More, the protagonist in the story, says something about these swallow birds, it’s important to look around the rest of the text to see what else is going on. They serve as symbols, and paying attention to the martins helps us better understand the story and Tom More.

In one scene, More, a physician, is listening to his patient Ted Tennis describe what’s plaguing him. More tells us Ted suffers from “massive free floating terror, identity crisis, and sexual impotence” (33). However, as Ted runs through his symptoms as though reading from a textbook, More notes that the two, “watched the sooty martins through the doorway come skimming up to the hotel – it helps with some patients if we can look at the martins and not at each other” (33). While Ted Tennis discusses his symptoms as though he’s ordering fries and a burger, we can pick up by way of the martins that what Ted is talking about – confessing, even – is more uncomfortable then he wants to admit. His studying of the birds and not making eye contact with More is a non-verbal cue that something else is going on.

In another example, Walker Percy uses martins, the bullbat nighthawk specifically, as a symbol of foreshadowing. It is at night when Tom More notices the birds “skimming in from the swamp sliding down the dark glassy sky like flecks of soot. Soon the bullbats will be thrumming” (152). In this scene, More is having a conversation with Leroy Ledbetter, a good and friendly man who, More learns has done something wrong, and the realization that a good man can do evil things terrifies More.

The introduction of the bullbat a few sentences before Leroy Ledbetter is significant because of the kind of bird it is. They cannot be seen during the day, and it’s their “thrum” at night that best identifies them. Finally, a bullbat’s beak looks as though an ant would have a difficult time getting into, but it is in fact deceivingly large. Percy uses this small, inconspicuous, thrumming bird to introduce a dark layer of Leroy Ledbetter’s personality.

In one part of the book, More is supposed to go visit a man named Charley, who is suffering from “acute depression”(39). More says he doesn’t feel well either and goes on to explain that “it is March 2, the anniversary of Samantha’s [his daughter] death and the date too of the return of the first martin scouts from the Amazon basin” (39). It might seem strange that More would place the same amount of significance on the return of birds to his daughter’s death, but the martins serve as proof of some sort of order in the world; which he is desperate for.

Scout martins are the birds that arrive early to check out the area for food and housing. If they don’t return, then the rest of the flock knows to travel because the area is livable. More is putting off going to see Charley because he is looking for evidence that this place where children die and evil persist is still livable.

The martins’ habitat not only serves as a symbol of order, where they take up residency shows that there is life in a seemingly hopeless place. For example, More sees the birds “nesting in the fenestrated concrete screen in front of Saint Michaels”(138), the church he and Samantha used to attend. Tom says this is the church he “ate Christ and held him to his word, if you eat me you’ll have life in you” (138). But “the center did not hold” (138), and yet birds still nest, life still stirs among the ruins.

One of my favorite things about discussing literature is finding something in a story that has a deeper meaning. Walker Percy’s use of martins helped me understand Love in the Ruins better. It also helped me think about how I can use symbolism in my essays to add depth, draw out my characters, and flesh out themes. Finally, it made me think of Catherine and her horses, and how I hoped I allowed her enough time to work out and explore life so that she could make some sense of the world she was growing up in.

Work With Me –

I now offer manuscript and essay critique, and would love to read your work. Interested? Details here.

Leave a Reply