A few days a week, I work with first and second graders to help with their reading and writing development, and this month I thought it’d be fun to write and draw a little journal response that integrates what we read, with something to be thankful for.

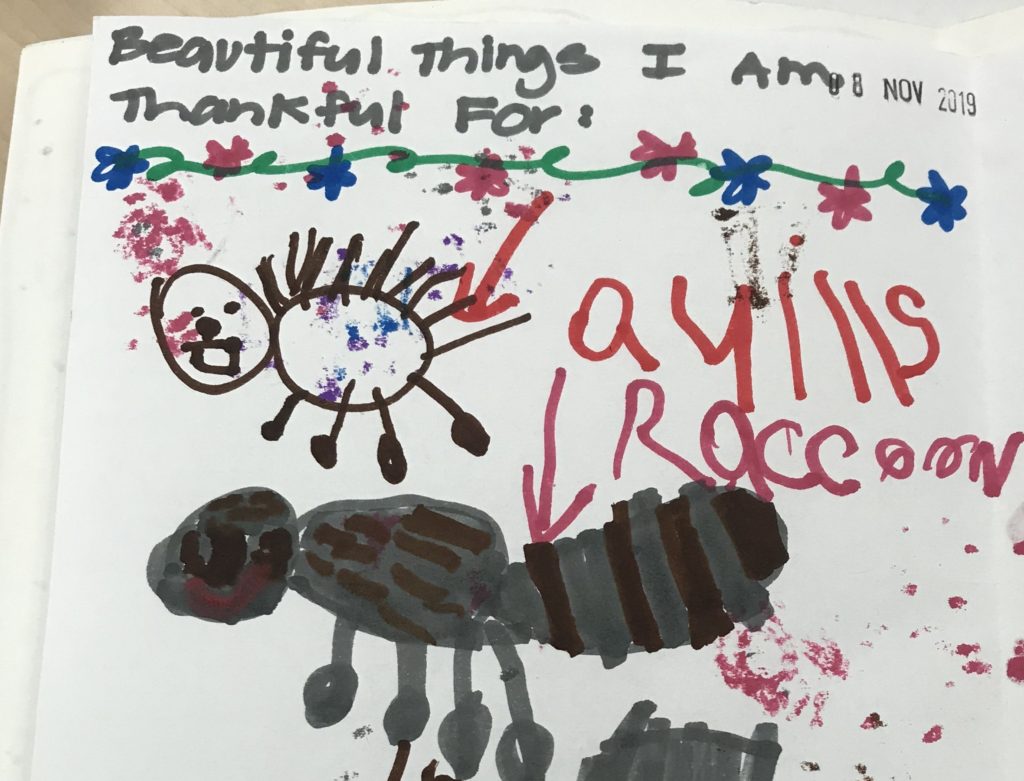

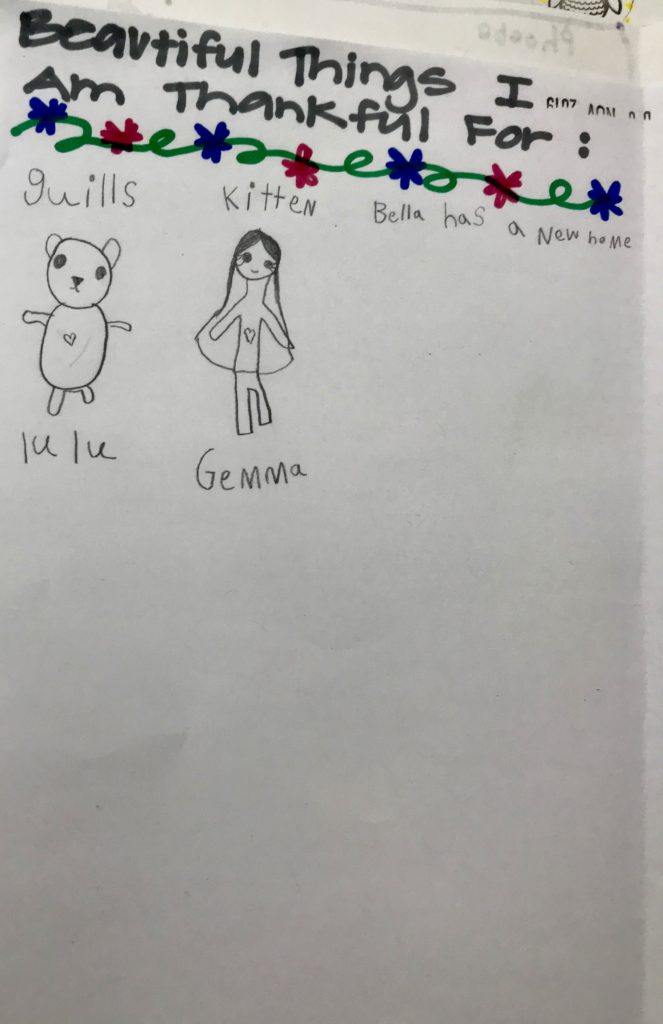

For example, a couple of first grade girls worked through the story, Beautiful Animals, a tale about a bunch of creatures celebrating how beautiful they are. Except for the porcupine. He doesn’t think he’s beautiful because of his quills. It takes a girl porcupine to tell him that he isn’t ugly; that she thinks he is quite lovely.

“Awww,” I said at the end of the story. “That’s so sweet.”

“Are you gonna cry?” one of the girls asked.

“Probably not,” I said,” but I do like a good love story.”

She shook her head and rolled her eyes. “They’re porcupines, Mrs. Feyen.”

Love is love is love, I wanted to say, but instead, gave them their Thanksgiving journals. That day’s prompt: What beautiful things are you thankful for?

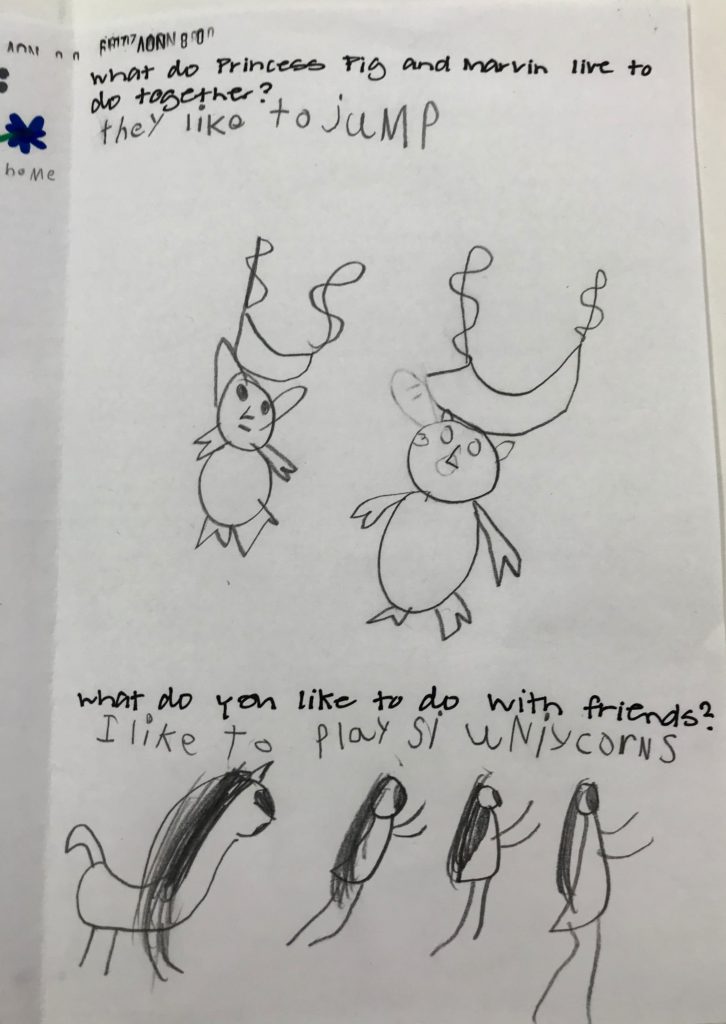

We read Princess Pig and Marvin, a story about two very different pigs who love to hang out together, and I asked students to write what they like to do with their friends.

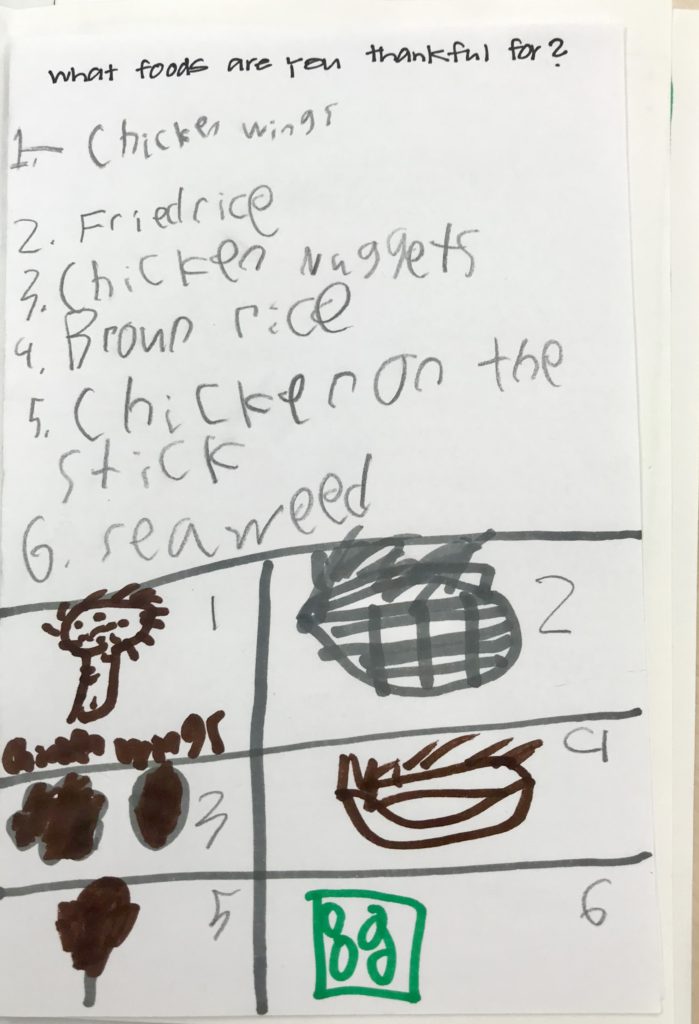

A group of second graders read The Giant Carrot, about a grandpa who loves to tend to his garden, and loves vegetables, especially carrots.

One day, he grows a carrot so enormous, it took grandma, the cat, and a mouse to pull it form the ground.

“OK, so this is fiction,” one student said.

“Right, this is not true,” another student confirmed. Both of them were pointing to the picture of the carrot and looking quite concerned, and I realized they had no issue with the cat and the mouse both standing on their hind legs and using their strength to help humans, rather, it was that perhaps there could be a world where vegetables grow to that size, thus taking over lunch and dinner as we all know it.

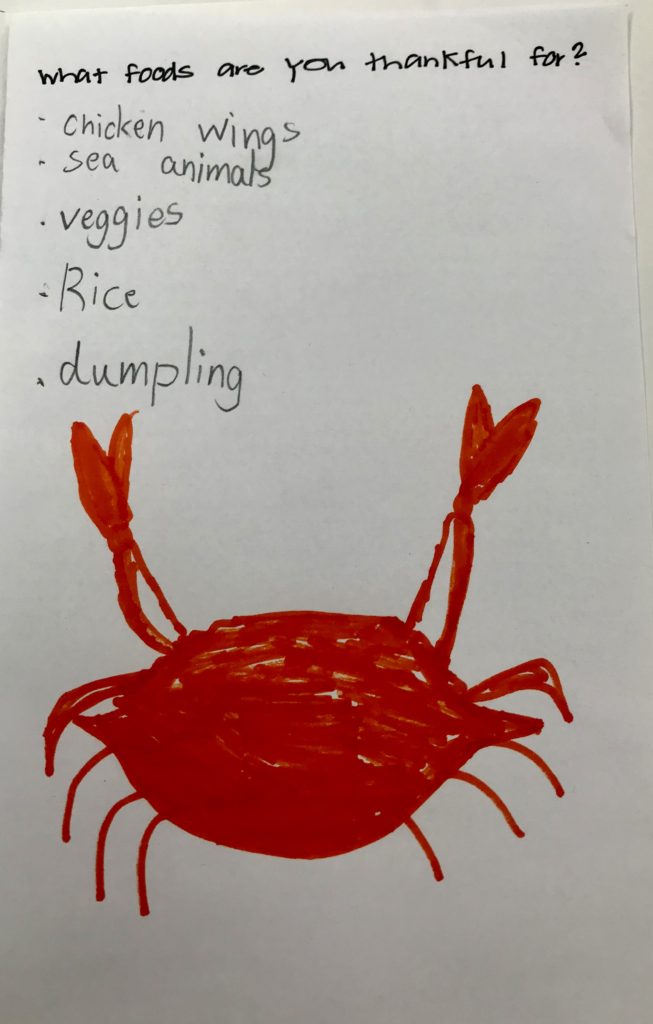

For this story, I asked students to make a list of foods they’re thankful for.

One girl, she loves dogs and consequently, any stories about dogs: Clifford, Henry and Mudge, Bark, Dog! We read these stories and it takes double time to do it because something she reads reminds her of her dog, and she’ll tell me about it.

“Mrs. Feyen,” she’ll say, pushing aside the book, and taking hold of my arm so I’ll listen. She tells me about a sweater her mom bought for her dog when the weather turned cold; that her dog was once lost; that it gets harder and harder to leave her every morning for school. Each of her stories has something to do with what she’s reading, and I listen because this might be my favorite part about reading – that our stories come from other stories. We’re all talking to each other, if we wish to. We’re all sharing pieces of ourselves, if we wish to.

But one look at The Giant Carrot, and my little friend gives a jolt, a lost, confused glance at me, and a shake of the head.

“I can’t read this,” she mumbles.

“Yes, you can,” I say, and I might not mean she’ll be able to read all the words – that’s what I’m here for – but she has to believe she has the ability to connect with this story like she has with the ones about dogs. If I can convince her of that, and she finds a connection with a story she wasn’t planning on connecting with, maybe she’ll begin to see the infinite ways there are to find out who she is, how she thinks, and how she might walk around in the world.

I uncap a highlighter when she stumbles on “grandfather.” I highlight “grand,” and ask her if she knows that word. She does. I hand her the highlighter and she highlights the rest.

“Grandfather,” she says.

“You got it,” I tell her.

She continues. Sometimes she sounds out the words, sometimes I help her. She’s exhausted when she gets to the end of the story when the carrot is finally pulled from the ground.

Exhausted, and not entertained.

I am second guessing my choice of story, and I almost end the lesson there, and tell her to go and get Henry and Mudge, but she asks about the Thanksgiving journal, the one she made a few days ago, the one I said we’d used everyday we read together in November.

The idea was a whim. I’d been looking through my plans for that day and was feeling a vacancy about them. Maybe the stories were stale. Maybe I was stale. Either way, I wanted to do something else. Something more. Something creative. So I came up with the journals.

“What’s the question?” she asks, still tired from the work of reading without having made a connection.

“Well,” I begin, “the Grandpa in the story loved vegetables, and carrots were his favorite,” I say and lean to get her journal from across the table. “So I thought we could make a list of all the foods we are thankful for.”

I feel a twinge of guilt about assigning a list and not a couple of sentences, but I remember listening to Marilyn McIntyre discuss the importance of making lists. “There’s always more going on,” and there’s a “tendency to drop into deeper places,” she said. Maybe this could be a tool for her when she’s stuck on a word, or when a story becomes too hard, or when there is seemingly nothing to connect with – the loneliest kind of reading.

“I have a lot of favorite foods, but I don’t know how to spell them,” she says, looking at her hands.

“I’ll help you spell them,” I say, and hand her a pencil.

“Tamales,” she says.

“Ahh, tamales,” I say as though I’m smelling them baking now. “Yum. Tell me how you prepare them,” I say leaning an elbow on the table and forgetting I said I’d help her spell a word that’s so much more fun to say than write.

“Well,” she says, pushing aside her journal and rubbing her hands together. She tells me about corn husks that are put on a hot skillet with garlic and chili peppers. She talks about butter and cheese, poblano peppers, black beans, and chicken. She mentions a sprinkle of cilantro.

“You’re making me hungry,” I tell her.

She smiles and picks up her pencil.

“When our family and friends visit, we like to make their favorite foods,” she tells me.

“That’s nice,” I say.

She nods and looks at me expectantly. She wants to know what to write.

“OK,” I say. “Here we go.”

And we begin.

Leave a Reply