I was part of a T.S. Poetry Press writing retreat this weekend, and led a workshop on the possibilities in writing conflict. This was part of my lecture:

I subscribe to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary “Word of the Day” emails with the idea – or hope – that I’ll use whatever word I learned in my writing that day. The morning I began to prep this presentation, the word was “silly season.”

Sorry to be redundant, but it seems silly to consider what this phrase has to do with conflict.

I learned though, that this the season we are in. Silly season happens in late summer. It originated in the mid-19thcentury when Washington DC and European governments took a break, and journalists didn’t have much to report on. Instead of leaving that space in the newspaper blank (or, here’s a thought – what if it was filled instead with poetry? What would that do to us?), journalists found rather ridiculous events to report on.

I lived in DC at a time when the Washington Post was delivered to my apartment door, and I remember the stories during silly season about tourists not using the escalators to and from the Metro properly. (The left side is for passing – not for holding hands with your sweetheart and discussing the many wonders of DuPont Circle.) Or tourists getting told off because under no circumstances can you bring food or drink on the Metro. There was a particularly amusing story about a group of New Yorkers who treated the Metro like the subway and tried to rip open its doors as the train was taking off. You might get away with that in NYC, but not in Type A-I’ve-come-here-to-do-a-very-important-job-DC.

Jesse and I moved to DC during silly season – a few months before George W. Bush was re-elected – and for most of August, I’d walk with him to the Van Ness Red Line where a giant piggy bank with the word “dreams” on its belly stood outside of the tunnel to enter the train.

There aren’t any great synonyms for “silly” in my thesaurus: idiotic, simple, empty, pointless, to name a handful, but I remember being delighted by that pig holding onto everyone’s dreams as they went to work. What if that was payment for riding the Metro? You’d have to share a dream you have for yourself, your friend, your partner, your children, and the pig would keep it safe for you while you descended underground, and walked past the violin player playing Vivaldi, or Mozart, or a Top 40 song dressed up in a much more complicated melody then we thought was capable. And when you stepped off the Metro in the evening, and made your way home, that pig would be the first thing you saw as you made your way out of the tunnel, and maybe you’d be exhausted from the day you just had and the miles to go before you can sleep, but you’d smile because you have this dream, and it’s been kept safe, ready for you when you are. It’s a silly thought.

Still, that’d be some pig.

When we moved, I didn’t have a job yet. I could’ve been looking for a teaching job months before we moved from our lovely apartment along the St. Joseph River in South Bend, Indiana, but I was in the part of my relationship with teaching where I believed I’d given all I could and was therefore done with the career at the ripe old age of 27. Plus, I was reading The Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants series, which takes place in Bethesda, Maryland, right down the street from where Jesse and I were moving, and in the stories, the main characters – four girls who magically fit and look fabulous and are also incredibly brave in one pair of jeans – often meet at a Starbucks on Connecticut. When Jesse and I moved, we lived on Connecticut, and instead of looking for a job, I decided I had to sit in the Starbucks that these made up girls who found jeans that helped them grow up sat in. The dilemma was there were at least seven Starbucks on Connecticut. I decided I must go to all of them and figure which one this imaginary story took place in, and so that was my career goal during silly season of 2004.

I can’t say I know for sure which Starbucks it was, but I enjoyed my project. While I sat sipping coffee, I always brought a book and a journal along with me. I was jotting down ideas for a “weblog:” a term I’d recently learned. I thought it would be fun to start my own and write about my DC experiences, books, and I didn’t know, maybe shopping. I so loved to shop. When I was younger, I used to dream that shopping could somehow be a job – like a vocation. Talk about silly.

Sometimes though, I imagine that 27 year old girl sitting in a coffee shop, searching for a story to insert herself into, a book scandalously creased in front of her, a pen in hand, and a cup of coffee in the other, and I wonder if that pig kept some of her silly dreams safe for when she’d need them.

(Here, I gave participants an example of a Silly Season news article, and we attempted to write a haiku from it.)

Will Willingham, in an essay on haiku, wrote, “It’s often said that haiku can be read in a single breath. Small wonder , then, that many find it to be a means to breathing, to focusing, to noticing. Haiku can help make you resilient, and it can help reduce your stress levels. It can be a means of expression which might otherwise seem impossible, and it can help a writer learn the beauty of an economy of words.”

What small wonders can we inhale that, when turned over for a moment and exhaled out, can make us resilient? This, I believe, is the possibility of conflict.

(Next, I gave everyone a news story that was not so silly, and asked that they write a haiku from what they read.)

August has never been a great month for me. It’s usually too hot, the bugs are too big, and nostalgia as thick as humidity follows me around, threatening to smother me. I don’t understand how I am nostalgic for a season that hasn’t ended yet, but here I am, saying to Hadley and Harper, “next month at this time, you’ll be in 7thand 5thgrade.” I’ll say it standing in the kitchen, slicing a pear for the girls’ breakfast.

They don’t need the pear sliced anymore, but I’ve gotten good at it, and I get satisfaction from the simple chore. I pull my grandmother’s small, navy blue bowls from a cupboard and with a sharp knife, glide through the fruit using my thumb as a stopping point, and the pear will thunk into the bowl, its green and creamy white flesh brightening up the navy like a lily pad in a murky pond.

I’ll serve the girls the pear at the dining table just off the kitchen and they’ll say thank you, but nothing about what will be going on next month at this time. They will be looking at their screens, breaking a rule I created but never enforce. “No screens at the table,” I declared one day when I was angry, and probably feeling scared about the monster that is Screen Time.

Or, they’ll be reading. Harper’s making her way through Two Towers, and Hadley’s gotten into the Divergentseries. Neither of them pay attention to the outside world when they’ve found a book they can’t turn away from, and for some reason, I don’t find this to be as monstrous as the words they read and stories they find on the screen.

Sometimes they do other things. Harper’s been working on a story that so far has filled up two journals. She tells me she prefers to write in pen or pencil first and then type it out. “I need to see it,” she tells me, as she attempts to explain why she writes first, and then types.

Lately, Hadley’s been painting logos from brands she loves or quotations matched with pictures or designs she comes up with. She will study what she sees on her phone, and then transfer it to paper. “Tiny Details Matter,” she painted one morning in stick thin, summer sky blue ink.

My Aunt Lucy was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer during silly season eleven years ago. I was seven months pregnant with Harper when I found out. I remember I was sitting on the kitchen floor, holding the phone and listening to my mom tell me about her sister with one hand, and with the other hand, holding my belly, my palm cupped on what I thought was Harper’s rump, or maybe it was her head – it was rounder than a knee or elbow, I knew that. I knew too, that Harper moved so much I often felt like I was being pushed on a merry-go-round, and whatever it was I was trying to hold on to wouldn’t stay where it was for long.

It would be easy and believable to say I was on the floor of our kitchen because that’s where Hadley was. Not quite two, the ground was the perspective for this little person making her way in the world, and I was often helping her make her way. But I was sitting on the floor in an attempt to close off everything else – all sound, all smells, I needed nothing else to touch me while I took in the reality of a beginning, and of an ending merging and tangled.

This is how August has felt for me – a swirl of beginnings and endings, like a summer wind that hints at fall, my daughters’ bare feet that no longer dangle from their limbs when they’re sitting on chairs, but are now flat on the ground, a subtle but noticeable earlier sinking sun – I have felt these things, save for the observations of my daughters, since I was a little girl, though it was heightened and defined for me that silly season of 2008.

August is a mess, and I hate messes. I like nice, neat, color-coded categories, straight lines, perfectly round circles, if plates with sections for the different kinds of food served at each meal were trendy I would buy them – I want nothing to touch what it is not supposed to touch. This is the same for endings and beginnings. I don’t like that phrase, “both/and.” It makes me uncomfortable. I don’t sit well in this mingling of opposites, though now, almost two decades away from that girl looking for stories in a Starbucks, who had unformed, nameless, dreams, I am learning that this uncomfortable combination, if I can sit with it long enough, is the soil for where stories begin to grow.

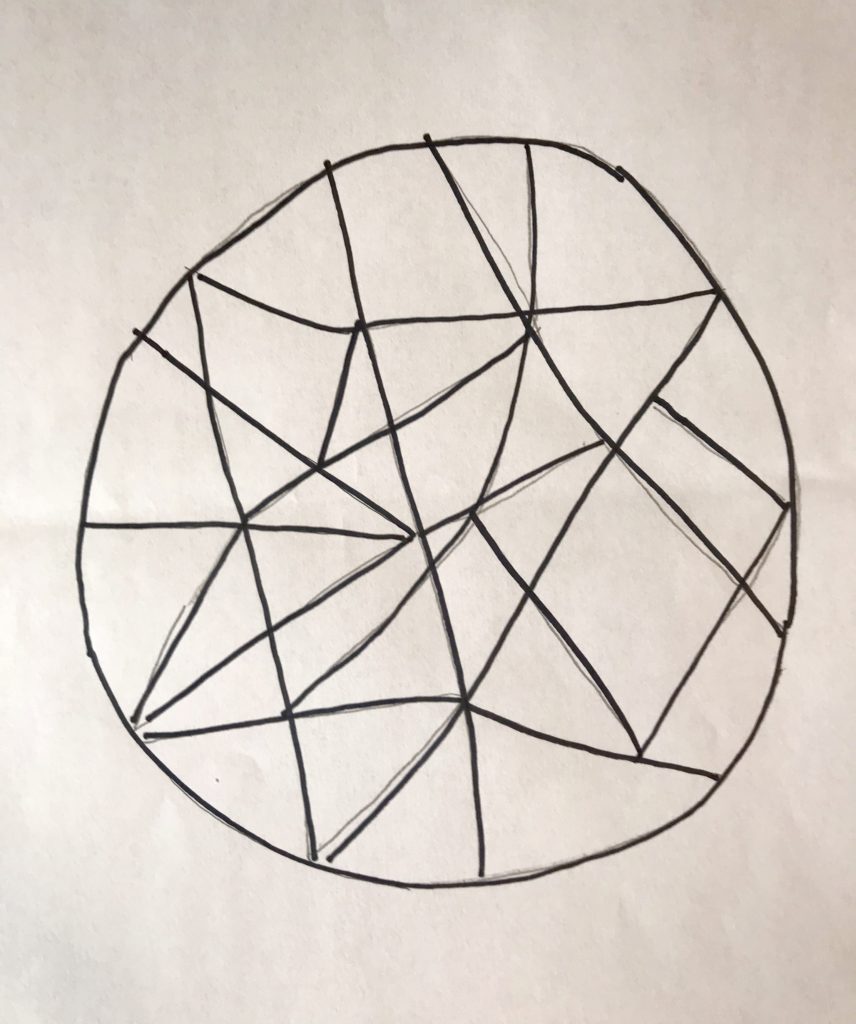

Harper actually has a method for this. She practices it often while I’m reading to the girls at night. She’ll draw a black circle on a white piece of paper, and then draw lines inside the circle.

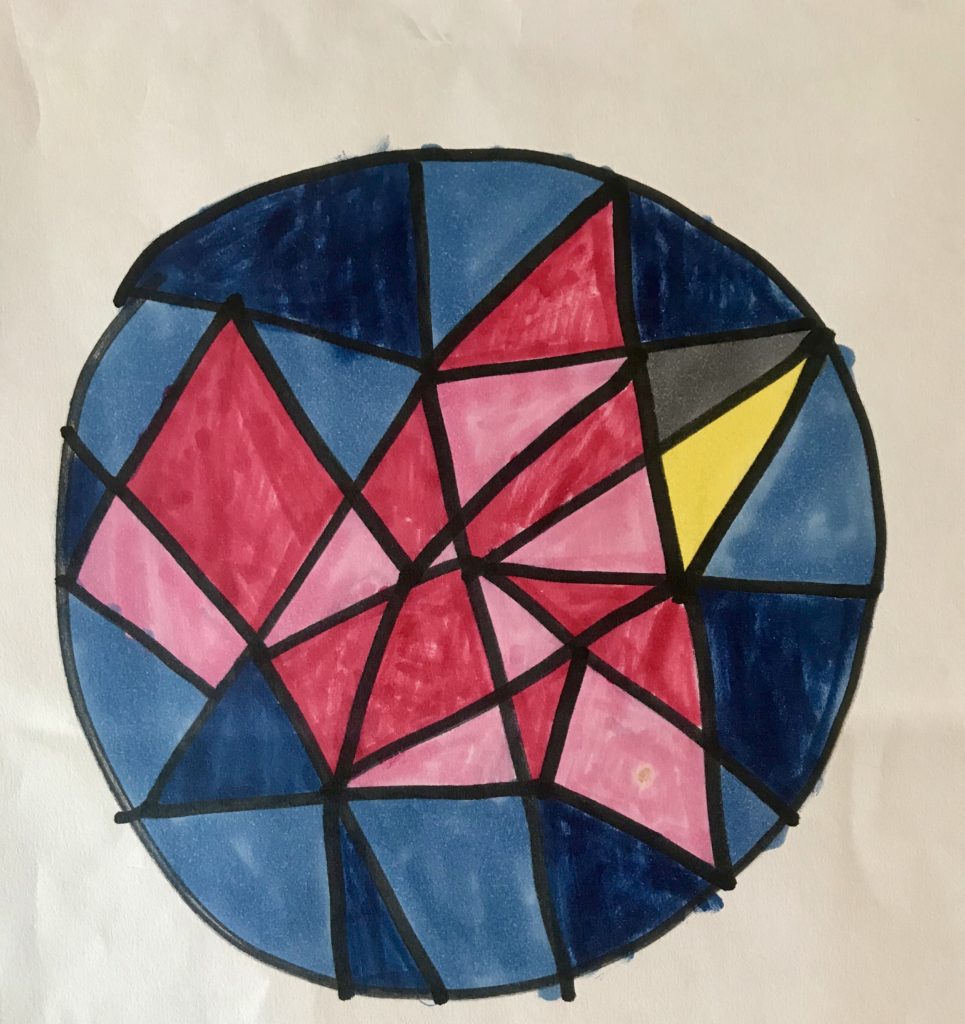

Then, she begins to color the shapes the lines made. One evening, she made this:

“Harper,” I said when she showed me the cardinal, “did you know this is what you were making?”

“No,” she said. “I just look at what’s there and see what I can make with it.” She looked at the bird for a moment, while I looked at her, and then she said, “We’ve been having that cardinal visit us recently in the backyard. I must’ve been thinking of him.”

I read somewhere or I was told that an artist is someone who doesn’t look away. Perhaps the possibility of conflict is actually the possibility of art. What is it we can see and in turn pull out of and create from the messes we are in? What brims to the surface of what we decide to keep paying attention to?

(We all tried the cardinal activity, and wrote another haiku from what we drew – or how we felt while we drew.)

One evening last week, Harper and I were home alone. Dinner was over, and the kitchen cleaned up. If it were a school night, it would’ve been a fine time for PJs and perhaps some reading or a show on TV. But we are not on a school calendar and summer is not over yet, and so I asked Harper if she wanted to go to the pool. She replied by pulling on her bathing suit, still wet from when she was wearing it a few hours ago, and yanking a towel off the back deck, also still wet, and off we set.

A friend of mine was there, blowing up an inner tube the size of a small, but comfy houseboat. Her children were eagerly waiting for her to complete the task so they could set sail.

Harper ran off to the diving boards and began practicing her back dive – a new skill learned this summer. My friend’s kids, after a few more minutes of inquiring when she’d be finished with the S.S. Pirate Ice-Cream decided it would be best for the livelihood of everyone, if they jumped in the pool and left their mama alone to get the job done.

My friend and I sat together, I holding a cold drink, and she with an inflatable lifeboat draped over most of her body. The slowly setting sun was bright and Harper looked like a stick figure soaring off the diving board, the water that splashed when kids jumped in looked like crystals, and I don’t know how she had the lung capacity for it, but we began to talk as she worked on inflating the boat. We talked about work, about our children, and my favorite, about our memories of growing up.

As the boat grew thicker and sturdier, she would cover the valve with her thumb, lean back on the blue Adirondack chair, and tell me about a best friend that moved away just before she started middle school. I took in a sharp breath and nodded, remembering my own painful navigations through those years. I watched Harper toss one of those weighted rings into the water. She waited for it sink to the bottom of the pool, then dove in search of it.

“I used to tell myself, all I need is one good friend and I’ll be OK,” I muttered to my friend as she began again to fill the boat. Harper popped out of the water, smiling, the ring in hand. She swam to the edge of the pool, hoisted herself out, and threw the ring, playing the game again.

Not that I question my friend’s resilience, but I didn’t think that boat was going to float that night. Still, I sat with her as she continued to take deep breaths in, and I talked and listened as we tried to make sense of the ship that is motherhood and our children while remembering our past – tiny lifeboats on the horizon that when we continued to search for, when we refused to look away, became clearer.

“Good enough,” my friend said giving the boat a few pounds with her fist, and then tossing it into the pool. We sat in silence for a minute and then Harper rose from the water shivering – reminding me of the Polar Vortex a handful of months ago, and the changing weather as this summer begins to make its last gasp.

I wrapped a towel around her and we watched as the boat drifted away from my friend’s children, unnoticed, and towards a father and his son who was looking at the boat skeptically and fearfully, and also, as though everything he had gone through in his two – year – old life had prepared him for this exact moment. His dad sat him on the boat and pushed, and the boy’s face went from pure terror to delight in seconds. Who in the world could imagine such a glorious feeling as gliding from one end of the pool to another on a summer’s eve?

We laughed at the boy’s exuberance and maybe of our own memories of experiencing something so silly and wonderful for the first time.

The father heard our chuckles and apologized for taking the boat.

“Are you kidding?” my friend said, “That’s what it was made for!”

Harper shivered again.

“Time to go?” I asked her, hoping she’d say she wanted to stay and swim. I wanted to sit with my friend longer while the sun set. But she nodded, and her answer made her shiver again.

We said our goodbyes, my friend and I, and made our way home, while I watched for changing leaves and Harper searched for four leaf clovers. She’s the only one in our family who can find them, and she’s sure it’s because of her belief in fairies – legend has it that spotting a four-leaf clover means a fairy is nearby. The clovers are their way of communicating – of saying hello – to those who care to look. It’s silly, I know, but we have fairy doors all over Ann Arbor, and as far as Harper’s concerned (and maybe me too), that’s proof these creatures exist.

It’s hard to tell where silly ends and belief begins. Perhaps these things are tangled, too. Perhaps that’s the only way to breathe, to inhale the silly and serious, the ridiculous and the wise, the dippy and the sane. Perhaps our taking them in is how they intertwine, and they fill us up, so that we are able to breathe out, and set sail.

Leave a Reply