“Mrs. Feyens I can’t work today because I’m not doing good because just now Maya tried to kill me on the tire swing.”

“I did not try to kill you,” Maya says calmly, scraping nail polish off her nails. It’s hot pink with glitter in it. I like it.

“Killing doesn’t happen in school,” Joe tells everyone. “Throwing up does. That’s what happens on the tire swing.” Joe puts his elbows on the table and cups his hands around his mouth. “Throw-ING up. Not kill-ING.”

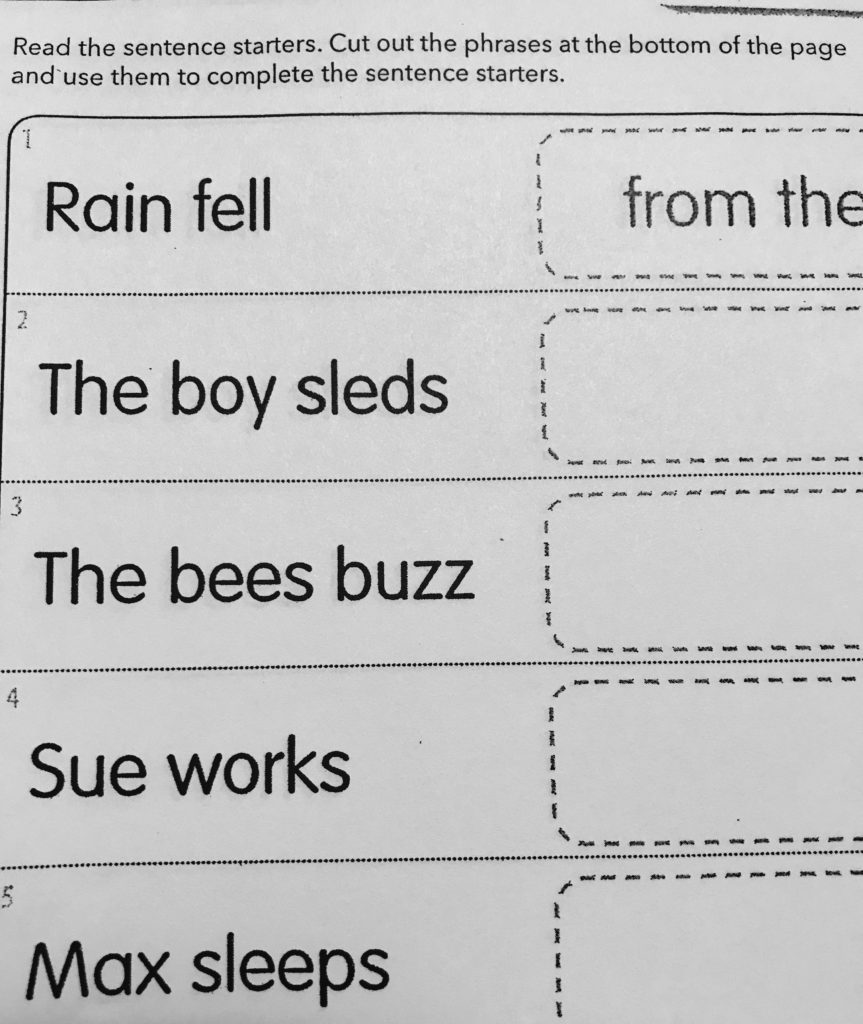

I hand out scissors for them to cut out the bottom of a worksheet. We are building sentences – taking a bunch of different phrases and matching them to see if they make sense:

Maya tried to kill me on the tire swing.

I almost threw up on the tire swing.

Which one makes more sense?

The kids are quiet while they cut, and I look at their hands. They’re still toddler chubby, but with faint signs of what’s to come; what it is they will be able to do. And will they remember learning to cut? Will they remember holding on to a rope for dear life while they spin and spin and spin around in the world as the snow falls thick and fat on their eyelashes and in their hair so that soon they are so dizzy they think they will die?

Pieces of paper float to the ground and drop to the table, and Nadia, she’s the one who was almost killed on the tire swing, begins to pick them up. She puts her scissors down, stands up, and crumples pieces of paper in her hand, walking around our table from student to student, and then to the trash.

“I notice you are helping us keep our area clean, Nadia,” I say. I’m supposed to use observing statements: I notice, I see, I understand. I’m terrible at that. I want to exclaim, “Nadia! You’re helping! Nobody asked you to but you did it and that’s wonderful! I’m so proud of you! I’m so thankful! Thank you!” My inclination is to do the same thing when the bad stuff happens: “Stop that! Cut it out! Are you insane?” That’s no good. I need to stay even-keeled. That’s a hard thing for me to do, but I’m trying, and I try with Nadia.

“Since you’re helping us, can I help you cut the rest your paper?” I reach for her scissors and paper, but don’t pick them up. I wait for her cue. Nadia, on the way to the garbage can, stops and looks at me, then nods. I begin to cut.

Nadia returns to her seat. She is sitting next to Maya. They always sit next to each other. Maya doesn’t read as well, or maybe as fast as Nadia does, and Nadia says the words – loudly and exuberantly – while Maya is still sounding them out. I assume it drives Maya crazy, and I think about Maya pushing Nadia on the tire swing.

“Thank you for throwing my trash away,” Maya says to Nadia.

Nadia nods again, and straightens out the strips of paper in front of her.

“So what we’re trying to do,” I say, pointing to the mess of words on the table, “is match up all these phrases and see if we can build sentences with them. Who wants to read one?”

“Ooooo! Mrs. Feyens! Mrs. Feyens! Pick me!” Joe yells even though he is an inch away from me.

“I’m having a successful day, Mrs. Feyens,” Joe tells me, but doesn’t begin to read. “I really am, and I’m going to keep having a successful day, and anyway, last week was my birthday and I turned 7 and we had a party with cake and music and presents and I got a football. I love football, Mrs. Feyens do you love football? Which team do you root for U of M, or MSU?”

“Joe, will you read the first part of this sentence?”

“I will because I’m having a successful day.” And so Joe leans forward like he’s about to pray and reads – slowly, carefully: “The bees buzz….”

Everyone looks at their cut sentences, searching for a match.

Nadia goes first. “I know! I know!” She’s shaking a piece of paper above her head. “It’s ‘in his bed!'”

“Bees buzz in his bed,” I say. “That sounds terrifying.”

“It’s ‘in their hive,'” Maya says, pointing to another piece of paper.

“And anyway, I’ve seen a hive,” Joe begins. “My daddy hit it with a stick and bees went everywhere and he got stung but I saw one bee and he flew away.” Joe sticks up one finger and makes curly cues with it holding his finger centimeters from my face so I’ll see what he means. “So Mrs. Feyens, I followed it.”

I begin to cut pieces of tape so students can build their sentences, and I pass them around.

“I followed that bee to the flower, and Mrs. Feyens, I leaned in close, and I watched the honey being made. I saw it all, Mrs. Feyens!”

“That’s amazing,” I tell Joe, and I wonder what part of his story is true: That he saw a hive? That he followed a bee? Watched it work a flower? Maybe he tasted honey so sweet on peanut butter or biscuits with pats of butter, or dropped on his fingers that he tasted and thought, Where does this come from? How did this come to be?

“Mrs. Feyens, my tape is stuck on the table,” Nadia says. “I can’t get it off.”

Maya looks at Nadia; looks at the tape on her finger, and looks at Nadia again.

“Here you go,” Maya says, offering her piece to Nadia.

Nadia looks at her. She nods, and takes it.

Maya looks at me. I am smiling.

“That was really nice,” I say, handing her a new piece of tape.

“Thank you,” Maya says, taking the tape and sticking her sentence together.

I adore how you take such simple, overlook-able moments and turn them into gold-tipped stories.

Build a sentence, build a story. One line at a time.

You are amazing, Callie.