It’s dark at 7am these mornings, and it’ll only grow darker. Soon, I won’t drive right towards the sun because the sun won’t be up; I’ll probably get to work faster because its light won’t be in my way.

I am sitting at the kitchen when Jesse comes in and says, “Smells good in here,” and walks towards me to see what I’m having for breakfast.

“It’s sourdough toast with pumpkin butter,” I start to say but I can’t finish because I’ve begun to cry. He puts a hand on my shoulder.

“It’s OK,” he says. “You’re OK.”

I’ve been up for almost two hours trying to write. Jesse gets up with me and sits on the couch next to my desk, and we work silently. This morning though, I was fidgety – slamming notebooks, opening books then shutting them again, shifting in my chair, snapping at Jesse for typing on the computer too loudly.

“You need a break,” he’d said.

I’m not sure a break from writing is the right thing. I’m scared that if I stop, I’ll like having the space free up in my schedule and my brain so that I’m not writing in the margins of my day, and I’m not always thinking about writing when I’m at a soccer game, getting groceries, at a party, sitting in church. Maybe I’ll like that life is more peaceful and I’m less haunted.

The other reason I don’t think I can take a break is because writing helps me work out what’s going on. I can see what I think and how I feel when I write. What’s more, I can change my mind about how I think and feel. Writing is necessary and redemptive.

There’s just been too much to process lately. First, it was the end of summer. I still carry that with me, even though it’s been a month since the girls and I go our separate ways each day, and there are no lingering scents of Coppertone and chlorine in the air. No more after lunch bike rides. No more late afternoon trips to the library. I need to write about those days so I can hang on to them, but also make space for the good things that are happening now: conversations on the way to soccer and ballet and piano practice, re-learning long division, and baking apple pies (Hadley makes the best crust, and Harper has found the perfect combination of cinnamon, clove, and nutmeg to put on the apples for baking). Everything these days is go, go, go, and I’m noticing the hydrangeas out front are starting to die, and I’m getting afraid because I remember last year, and I don’t want it to happen again.

But enough about me. Hurricanes have torn through the shores, there’s Las Vegas, and there’s #metoo, and every Sunday I think, “What’ll it be this week?” It seems there’s no light to drive towards, and all of us are speeding to our work that must get done, swallowing the sadness and the worry and even the joy because there’s no time to name it; no time to let it go.

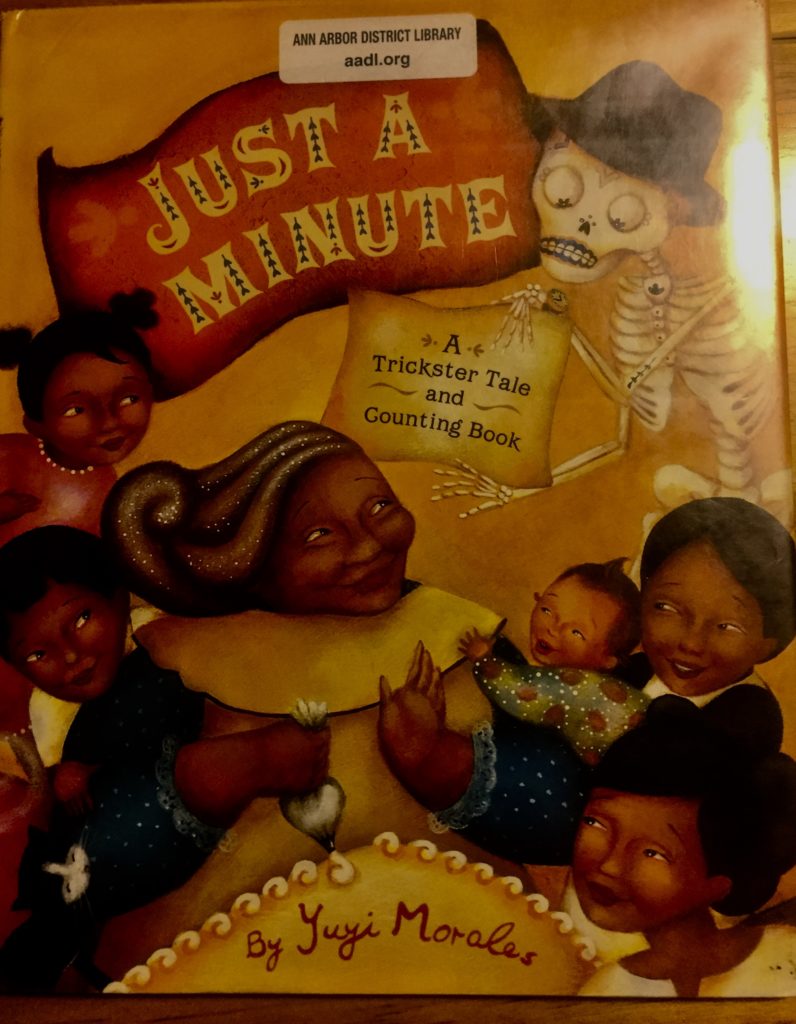

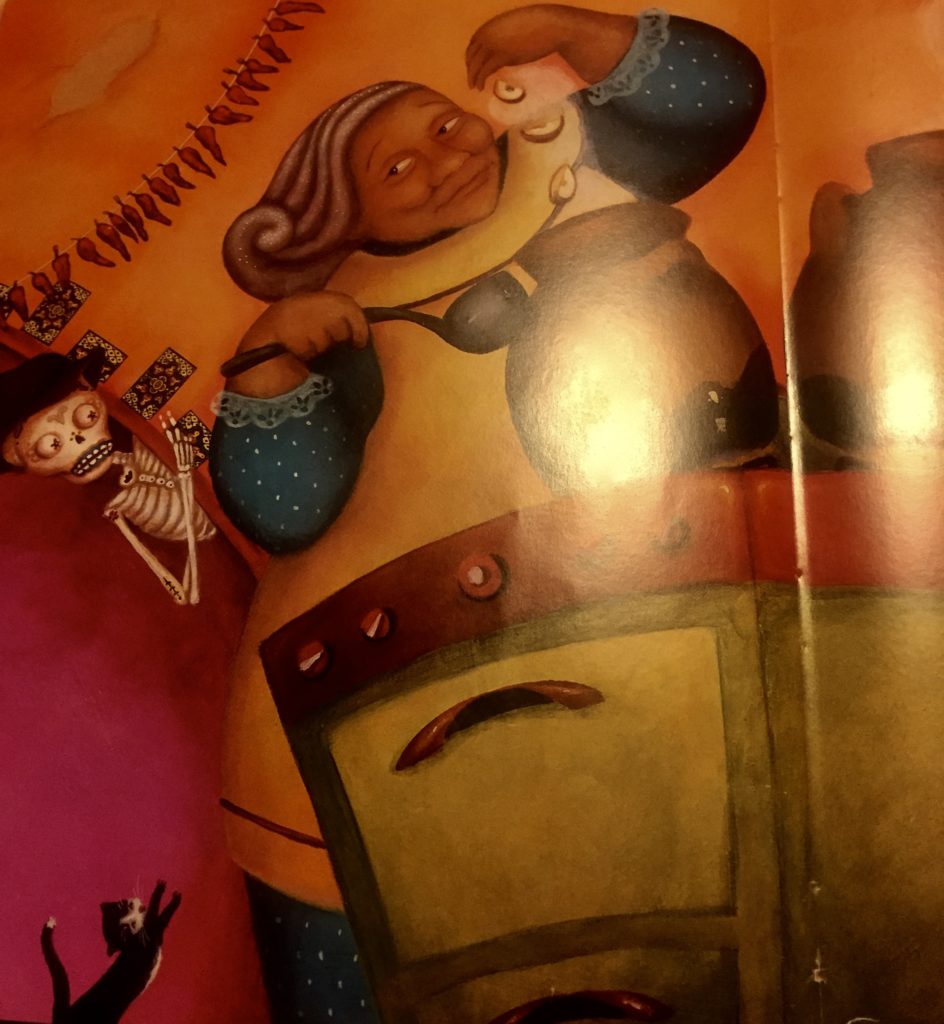

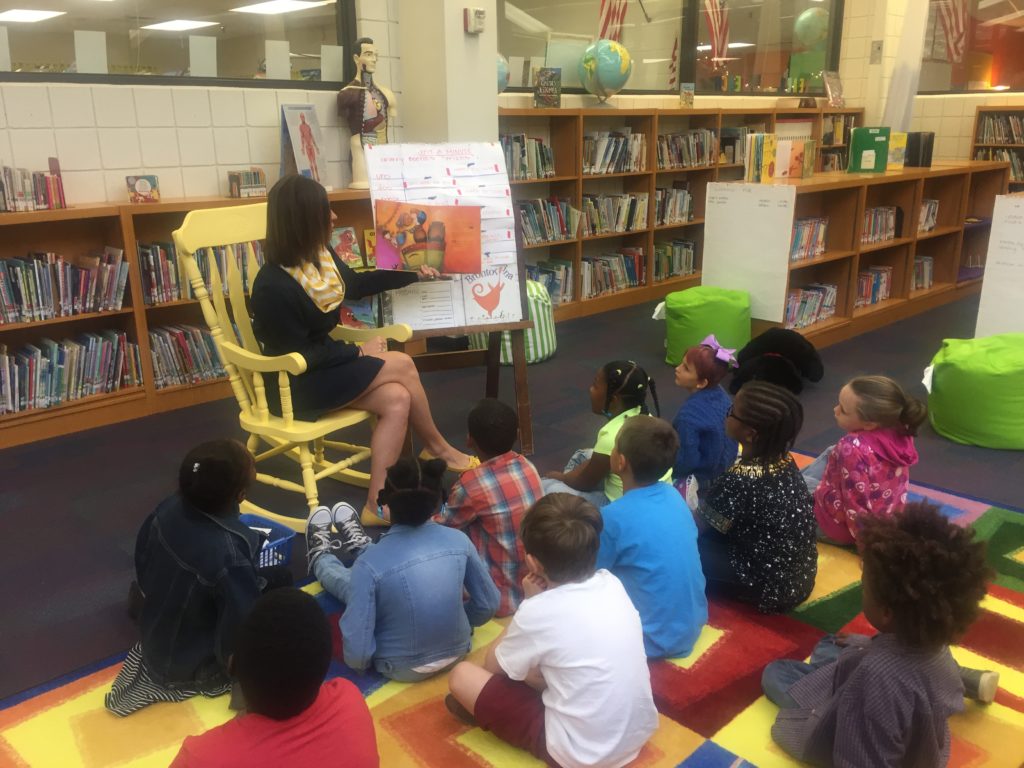

It’s Hispanic Heritage Month, so this week in the library I read Just a Minute by Yuyi Morales. It’s a story about a woman named Grandma Beetle who gets paid a visit by Senor Calavera.

The kids gasp when I show them Senor Calavera.

“He’s a skeleton!” they say. Many little brows furrow, eyes grow wide, some of them put their hands to their faces.

“He is a skeleton,” I say, and I say it in a spooky, sort of shocked voice. “Not only that,” I add, and point to Senor Calaver’s head, “’Calavera’ is Spanish for something.” I tap my finger on his head. “Do you know what it is?”

“SKULL!” they all scream.

“That’s right! Skull! Oh my gosh, you guys, I’m scared!”

“What’s he gonna do to Grandma Beetle?” they ask.

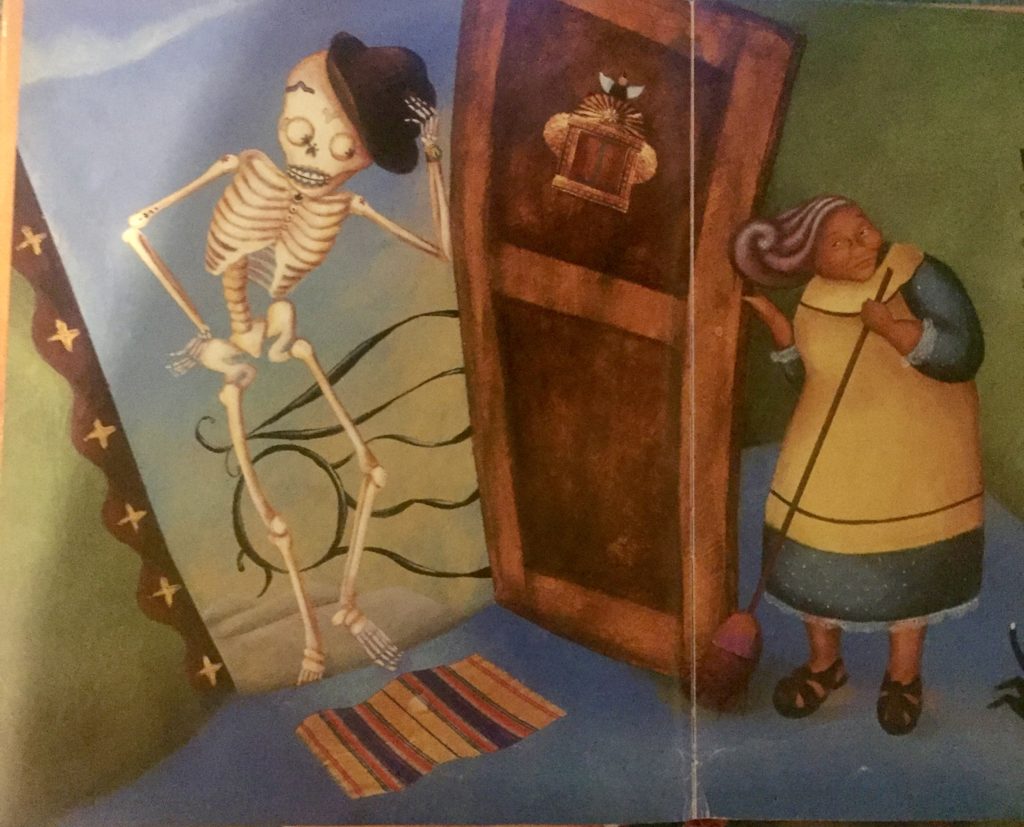

“Well, he tells her it’s time for her to go with him,” I say.

The room grows quiet.

“She’s goin’ to Heaven?”

“She’s gonna die?”

I point to Grandma Beetle, who’s looking right at Senor Calavera, and she’s smiling. “It says here this is a trickster tale, and I’m looking at Grandma Beetle, and wondering if maybe she’s going to trick Senor Calavera.”

“How old is Grandma Beetle?” one kid asks.

“I don’t know,” I say.

“She has grey hair,” the student continues, pointing to the cover.

“I think those are sparkles,” I suggest.

“Nope. That’s grey hair. She’s old.”

Yikes.

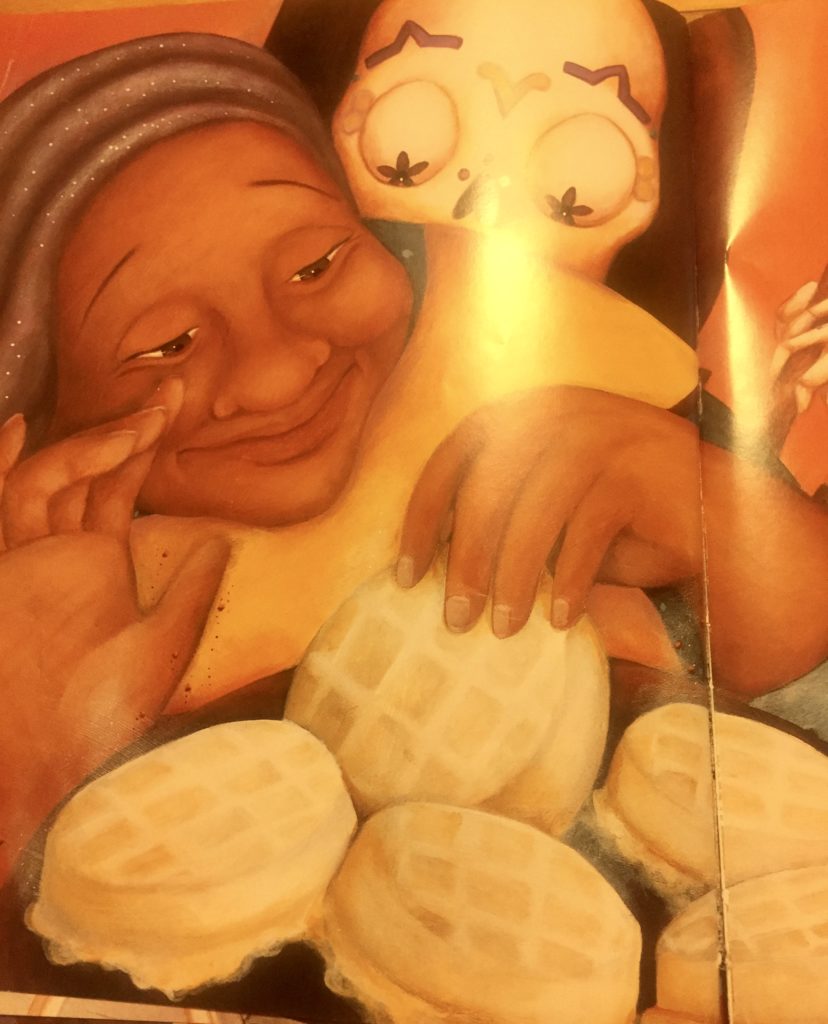

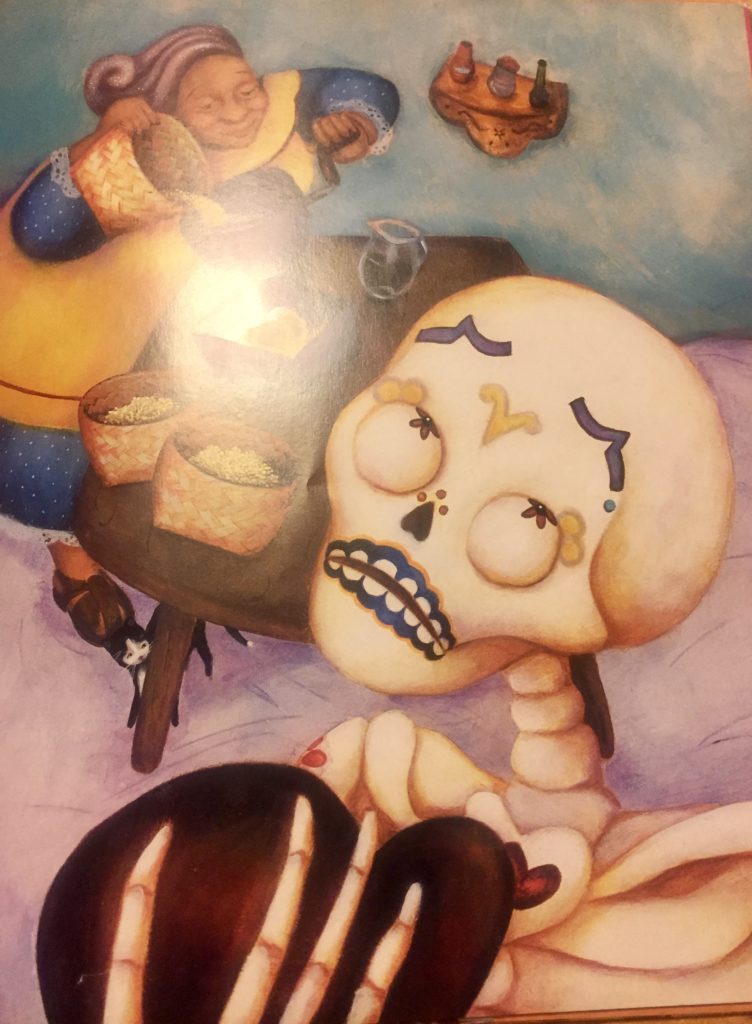

Turns out, Grandma Beetle strings Senor Calavera along. “Just a minute,” she says on every page, “I have to….,” and she explains a chore she has to complete. Senor Calavera waits, usually patiently, and on several pages, he helps.

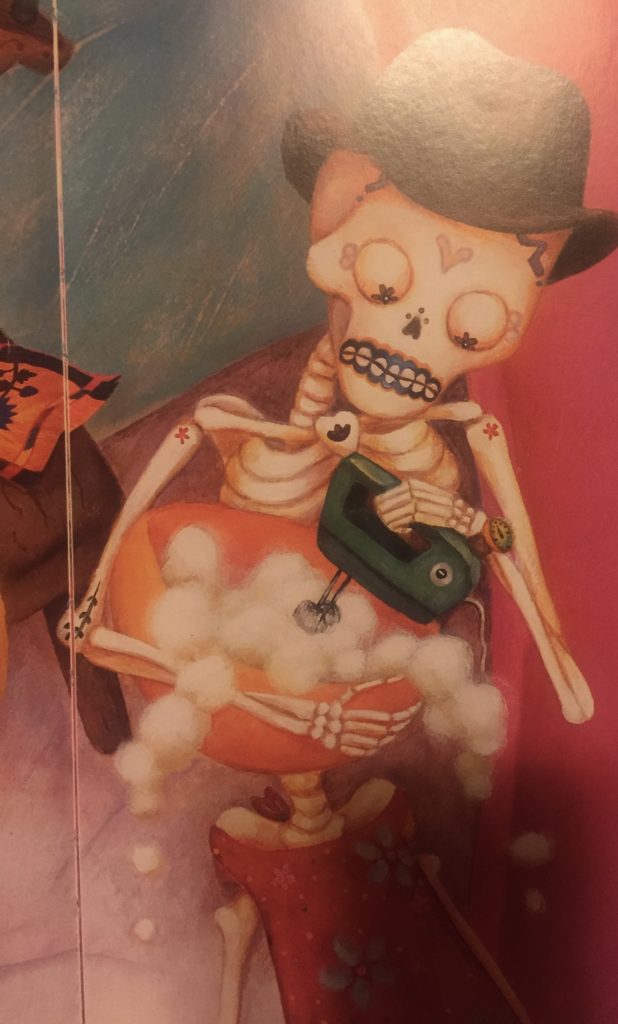

“He has flowers for eyes!” a student notices. I turn the book and look. “He does!” I exclaim. “And look, he has some decorations on his shoulders, too!” I show the kids and we all smile. We find a little bit of beauty in what it is we’re all afraid of.

The story is also a counting book, and for each excuse Grandma Beetle makes, a new number is added on.

“Can you show me quarto?” I ask, and hands shoot up. Tiny fingers splay out in four.

“Uh oh, you need two hands for ‘seis,’” I say, and kids look at their hands, figure it out, then show me six.

I point to some who are holding up five fingers on one hand, and one finger on another hand. Others hold three fingers on each hand, still others hold four fingers on one and two on the other. “Look at all the different ways of showing seis,” I say. “Just like there’s different ways to say a word.” Such a tiny thing to be joyful about, with death hovering around, waiting, but we revel in this observation anyway, and each number after six, students think about different ways to show me the same thing. I love watching them stare at their hands and figure out what it is they can do with them.

I think about Celena a lot while I read this story. Her family had the best parties. I remember standing in their living room, holding hands with Celena while she showed me how to dance to a Latin beat. The dance seems to start in the hips. In fact, the music makes you realize what your hips are there for.

Once, on a vacation I tagged along on to a Michigan lake house Celena’s family rented one summer, her parents took us out for pizza. It was a local joint, right on the border of Indiana and Michigan. The sign out front said that night there’d be dancing.

I don’t remember the music that was played, but it wasn’t the kind you needed your hips for. This was music that you barely lifted your feet off the floor for fear you’d maybe step closer to who you were dancing with, thus leaving an inadequate amount of room for the Holy Spirit.

All of us sat at our seats, kind of bored, kind of ready to make a bunch of jokes, when a man walked up to our table, smiling, and put a microphone up to his throat, then asked, “How’s the pizza?”

“Oh my God,” Celena said.

Her brother and his friends slammed their heads on the table, laughing. I think I said something equally appropriate like, “EW.”

Celena’s dad paid the bill and we left.

That night, her parents moved the furniture in the living room that looked out onto Lake Michigan, put on hip-moving music, and let loose.

My memory is of Celena’s mom grinning and dancing, a firecracker on the dance floor. Celena’s dad was dancing too, but my only memory is of him lifting her up and spinning her around. We all whooped and hollered and clapped along, but it is Celena’s mom’s confidence and smile I remember the most. Celena’s dad elevated what was already there. He helped bring it out. He’s done the same thing with Celena.

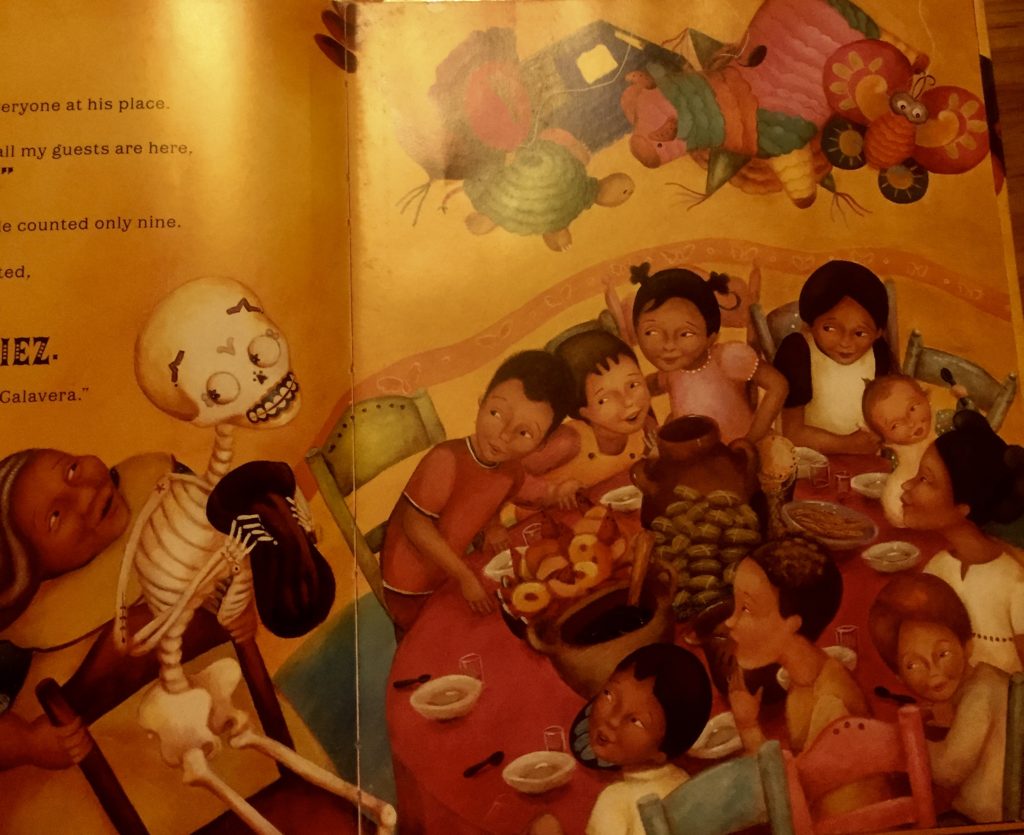

It is Grandma Beetle’s birthday and all her grandchildren come to the party she’s been preparing for.

“All my guests are here, and together they make ten.”

The grandchildren are confused. There’s only nine of them, not ten, but Grandma Beetle pulls up a chair for Senor Calavara and says, “Here he is. Diez.” Smiling, the class and I raise both hands in the air to show ten.

“The Diez Family!” one little boy says, and I think, sure, maybe being a family means pulling up a chair for who’s (or what’s) not been invited.

I think about telling Celena about the book I’m reading. I want to tell her I picked the story out because it’s Hispanic Heritage Month, and I want to acknowledge the best friend I ever had, and perhaps the best friendship that ever existed (we call our friendship a superhero). I don’t though because there is no time, and I am afraid that it doesn’t count because this is a Day of the Dead story, a Mexican holiday. Celena is Puerto Rican. Plus, Maria recently ravaged the land, and maybe a counting book poking fun at death isn’t appropriate right now.

I think Celena would like Grandma Beetle, though. Plus, it’d be nice to hear her voice. Something about her voice settles me down.

Once, when we were well into our thirties, I called Celena. It was a Tuesday morning, and I was driving towards Bethesda to take a writing course on how to write about motherhood. Hadley was three, and Harper was one, and they were at home with a babysitter with a binder full of instructions on how to put them down for naps, which TV shows are OK, and how much time to watch them for, which snacks are appropriate, how to peel the skin off an apple.

I called Celena because I’d decided what I was doing was stupid and selfish.

“I’m wearing heels, for crying out loud!” I wailed into the phone. “Plus, I left early because there’s a Starbucks across the street and I wanted to get a coffee and walk down Wisconsin to my class just like Meg Ryan does when she walks to her bookstore in ‘You’ve Got Mail.’ I’m a miserable person living in a fantasy. What is wrong with me?”

“Take a breath, Callie,” Celena said. “And since it’s you, take two.”

She told me the girls will be OK. That this is a good thing what I’m doing, for them and for me. “They need to see you pursue this dream, even if you’re not sure you can do it. They need to see you try.”

“This was not in the plan. I was supposed to be at home.” I said.

“Says who?” Celena asked.

“Me?” I said.

“So you changed your mind. Hadley and Harper need to see that, too.”

The story is over, and it’s time to check out books. The class gets up from the carpet, and starts towards the Clifford books, and the Mo Willems’ stories.

One child, a girl with floppy eyelashes and shaggy brown hair just like I used to wear it stands next to the rocking chair where I’m sitting.

“Hi,” I say, and she flinches, also something I would’ve done at that age. I probably still do it sometimes.

She points to the book then looks at me, barely lifting her head. I smile, and hand her Just a Minute,” get up from my chair, and offer it to her. She sits, and opens the story.

She is learning English. The first book she checked out this year was a Spanish – English dictionary, so thick it seemed to groan when she gave it to me to check out. Now, she rocks back and forth and swings her legs as she looks at Grandma Beetle and Senor Calavera. I hope she’s found a story to make her feel more at home.

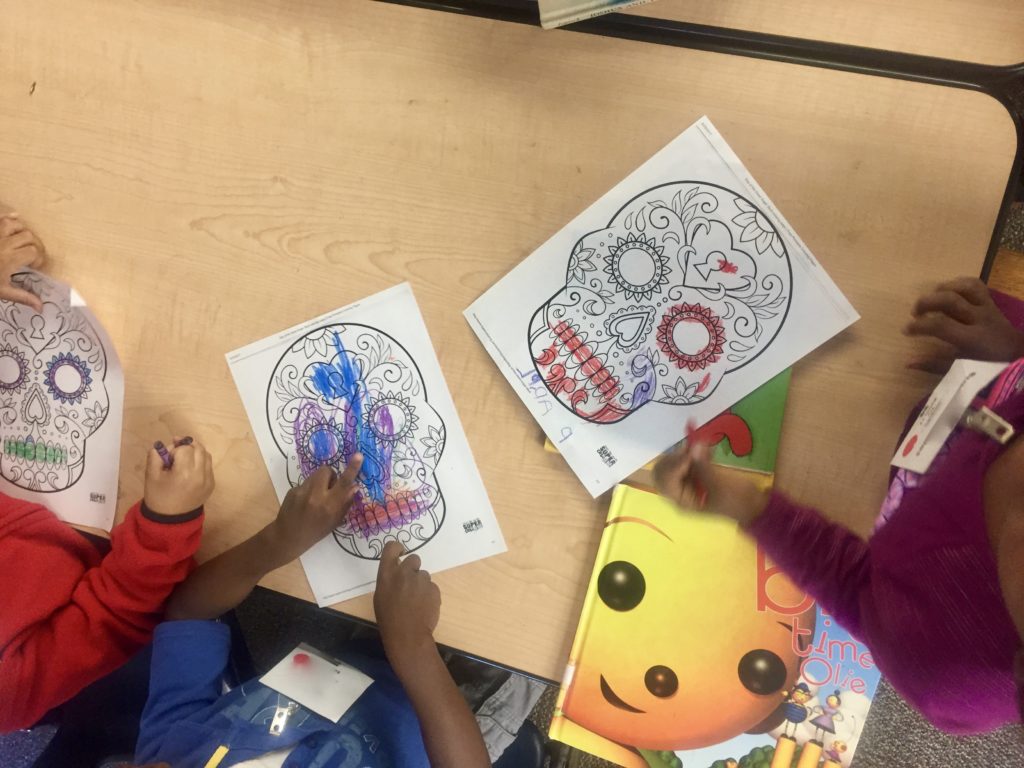

She reads and she reads while her classmates search for stories, and color their own Senor Calavera skulls.

I wonder if she is more like me, or more like Celena. I hope she is just like both of us – shy and bold, and looking for a friend to draw out both. Maybe she’ll find a friend in Grandma Beetle – someone who knows there’s work to do, who knows darkness spreads quickly these days, but who also knows it is no match for the light that is within.

callie ~ i just love the way you weave stories together when you write. it’s so interesting to think about what fills us up – how we can look for gratitude in our days – how memories can influence our present day life. i never really thought about what a gift our memories can be – how they can help us to unlock truths about today.