About a block from my school is a park with a playground. Several of the kids who walk home dash there after school, and watching sixth, seventh, and eighth graders goof off in that area is my favorite part of the day. I try not to look like a creeper, but I drive as slow as I can because watching them run and scream and climb and dodge each other puts a smile on my face.

Last Thursday, we got a bit of snow. It wasn’t a lot, just enough to turn 94 into a parking lot from the powdered sugar dusting that landed on the road. That day, as I was driving past the park, a boy was turning in circles down the sidewalk as he walked. He’d stop to study his footprints, and then begin spinning again. Studying and spinning, studying and spinning; I watched him and felt sad and hopeful at the same time and I don’t know why.

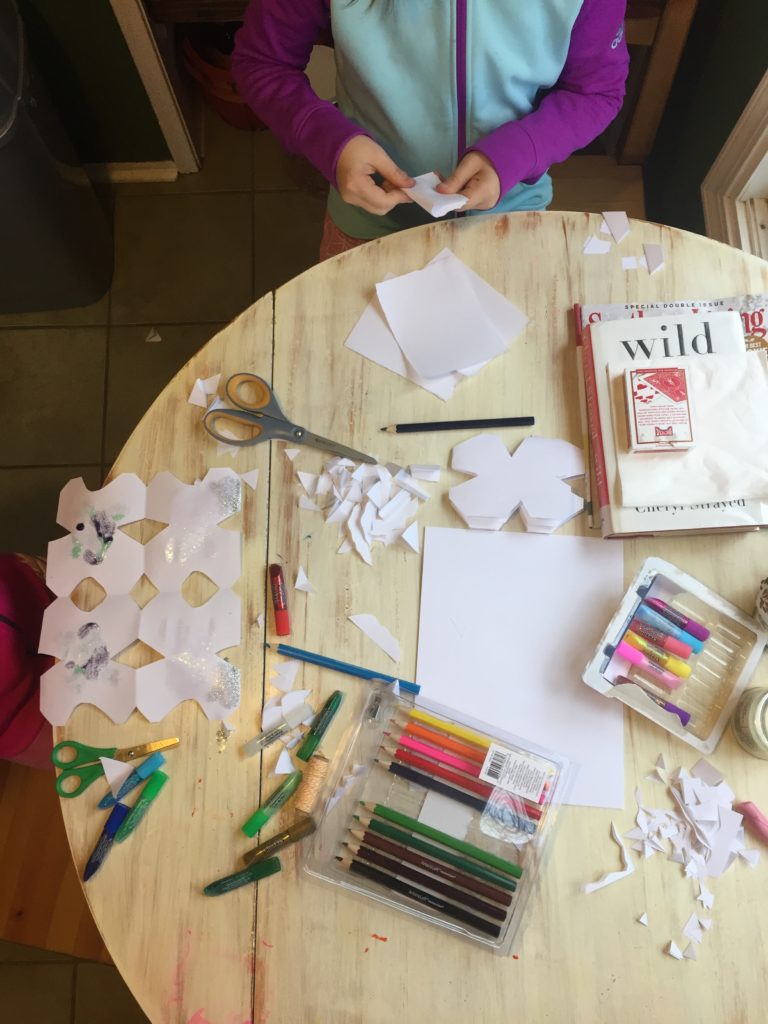

A couple Saturdays ago, I wanted to make snowflakes, but I forgot how to make them, so I looked up videos on YouTube. I couldn’t follow the instructions. I tried and tried, but I couldn’t figure it out. I don’t know why I can’t follow directions, but Harper walked into the kitchen to find me squinting at the computer with scissors and paper and asked what I was doing. I told her I wanted to make snowflakes, but I can’t figure it out.

“I can show you,” she said, and sat down next to me. I got rid of the computer and watched her little hands go to work.

“There’s no wrong way to do it,” she said, carefully creasing the paper, then looking up to make sure I was doing what she did. “It’s impossible to make a mistake,” she said as she cut out zig-zags and triangles.

We cut in silence for a while, then Harper said sort of quietly like it was a secret, “You want to know my favorite part about making snowflakes, Mama?”

“What’s that, Harper?”

“Opening up the folds of the paper and seeing what I did.” She carefully laid the paper flat and added, “It’s always a surprise.”

Hadley joined us and we decorated the snowflakes with glitter glue and colored pencils and stamps. We said, “Oooo! I like what you did! I want to try that!” We talked about school and Ann Arbor and we sang songs.

No two were the same, and I know that’s how the real thing is: no snowflake that falls from the sky is exactly like the same as the one that fell before or after or with it. Just like our fingerprints. Except, why not just make them all the same? Who cares that they’ve all been created differently? Who cares how the water mixed with the clouds and the cold or whatever happens to make a completely different design? And who cares that a boy who’s been sitting in class all day walks home past the park on the first day it snows and decides to twirl and mix his footprints with the thousands and thousands of different fallen designs on the cement?

I am reading Raymie Nightingale by Kate DiCammillo. There’s a librarian who is “lonely and hopeful” and he gives Raymie a copy of A Bright and Shining Path: The Life of Florence Nightingale because he thinks she’s a strong reader and could read nonfiction. Raymie is interested in doing a good deed, so she decides to read Florence Nightingale’s story to some people at an elderly home in her neighborhood. She brings her book to the place and meets a woman named Isabelle who is in a wheelchair and doesn’t see so well anymore, but Raymie isn’t so sure. “Her eyes were bright. She didn’t look like she was as blind as a bat. It was more like she had X-ray vision. Raymie could feel Isabelle looking right inside her. She squinched up her soul as small as she could and pushed it to one side, so that it was hidden.”

There’s a lot of talk of the soul in this book, and I like that. Sometimes Raymie’s soul feels like a “giant tent billowing out.” I know that feeling. It’s like those moments in elementary PE when the teacher brings out the multi-colored parachute and we all grab a bit and we shake it, or run under it, or try to keep a ball bouncing on it and we are all laughing at the thud the material makes and the wind is produces. Sometimes Raymie’s soul is small and tight, “like a pebble.” I know that feeling, too. The PE teacher balls the parachute up and wraps it nice and neat in its case, and I have to go to math and practice long division.

The day Raymie meets Isabelle and tells her she wants to read The Life of Florence Nightingale to her, Isabelle asks her why and Raymie tells her she wants to do a good deed. Isabelle says, “Why do you want to do a good deed? What is your purpose exactly?”

Raymie and Isabelle have a stare down at that point. Raymie has no answer for her, but Isabelle’s question about purpose prompts Raymie to make “her soul smaller and smaller. She imagined it becoming as tiny as the period at the end of a sentence. No one would ever find it.” I know that feeling, too. I felt my soul shrinking at every intention, purposeful question I’ve been asked this semester that I don’t have an answer to. I just want to spin around in the snowflakes and see what happens, but I think that there’s no time for that kind of teaching anymore (was there ever?).

To get to the church we are currently attending, we walk down a street with houses filled with college students. We haven’t seen any students, they’re probably still sleeping while we walk towards church, but the maize and blue banners hanging in the living room windows, the red cups on the porches, and the bikes in the front yards clue us in on whose streets we are walking down.

We talk a lot about college since we’ve moved. The girls are intrigued and have lots of questions. I tell them it’s like a great big Kindergarten. I tell the girls about the time I was in Kindergarten and we were making a snack called, “Ants on a Log.” It’s celery, peanut butter, and raisins and it’s delicious. Well, one kid broke his piece of celery when he was spreading peanut butter on it, and he started to cry. “Now you have two,” Mrs. O’Brien said, her arm on his shoulder and her long, brown hair was swept to one side so she could tell him the good news. That’s how college felt to me: I learned the possibilities there were with all my broken pieces.

It was my Sophomore year in college, and it was deep enough into the fall that the Michigan mornings nipped at my knuckles and cheeks as I walked to class; the air bit excitedly at what was to come.

I had a Navy Pea coat my parents brought me back from Boston, and I wore Penny Loafers. I slung a suede, green Jansport backpack over my shoulder, and I filled a travel mug with what I called a “poor man’s mocha,” a mixture of hot chocolate and coffee I could get at the Snack Shop for fifty cents. I sipped my drink and walked to my morning Philosophy class.

The class was held at the top of campus so that if you walked out of that building you had a great view of Science building, a few dorms, the cafeteria, and a nice sprawl of lawn that would soon be snow covered. I’m sure I stood there a thousand times but the time I remember most vividly was that crisp fall day after my Philosophy class when the cool weather foreshadowed something greater was on its way and two thoughts entered my mind: I don’t understand a word of Philosophy. I am happy.

I wonder if that’s how the boy felt as he spun in circles the day the snow barely fell. I wonder if the only reason no two snowflakes are the same is only to bring delight to those who care to examine them. The purpose is to employ delight.

The service at church is exactly like the one I sat through as a kid. I can close my eyes and I am 6, or 10, or 17; different and growing and changing each Sunday, but the doxology is the same. The Lord’s Prayer is the same. It is comforting to me. I can be confused and doubtful and afraid. I can be whoever I am going to be and this will not change.

I closed my eyes while the choir sang parts of “The Messiah,” and prayed, “Please let there be a place for me here. Please let me fit in here.” It was a wild prayer; I don’t know if my kids want to be here, if Jesse likes the church, I don’t even know if it’s what I want. This last Sunday, though, it’s what I felt, so I said something. I don’t understand a bit of this really, but I want to twirl in the snow and see what happens. I want to cut out random pieces of paper with no intent except to see what I did when I unfold the paper.

My favorite part of the service is the space between the Offertory and the Doxology when the organist intertwines the melody from the last hymn with the Doxology. Each Sunday the notes follow a different path but they somehow are scooped up and, “Hey, look! Those notes that were so beautiful in the one hymn are beautiful in this one, too.” Somehow the organist helps them find their place and we are standing and singing, “Praise God, from whom all blessings flow.”

All the blessings flowing and falling, and the best part is unfolding them and figuring out what they are and what it is we will do with them. What songs will we employ?

What I want to believe is there’s no wrong way to do it.

Me, other places: “Growing Up With Imogene Herdman” on Art House America.

“Playing with Fire” on Relief Journal.

Leave a Reply